Word Tag Quiz

Assessments didn’t match the play

Word Tag, a vocabulary game for kids aged 7–13, had strong gameplay but weak ways to measure progress. Placement relied only on grade level, which left huge gaps: some third graders read simple stories, while others tackled advanced texts. Teachers could assign word lists, but there was no validated way to confirm mastery. Quizzes existed, but they were shallow, slow to adapt, and didn’t feel connected to the game experience.

How could we measure vocabulary growth without breaking the flow of play?

Designing the diagnostic

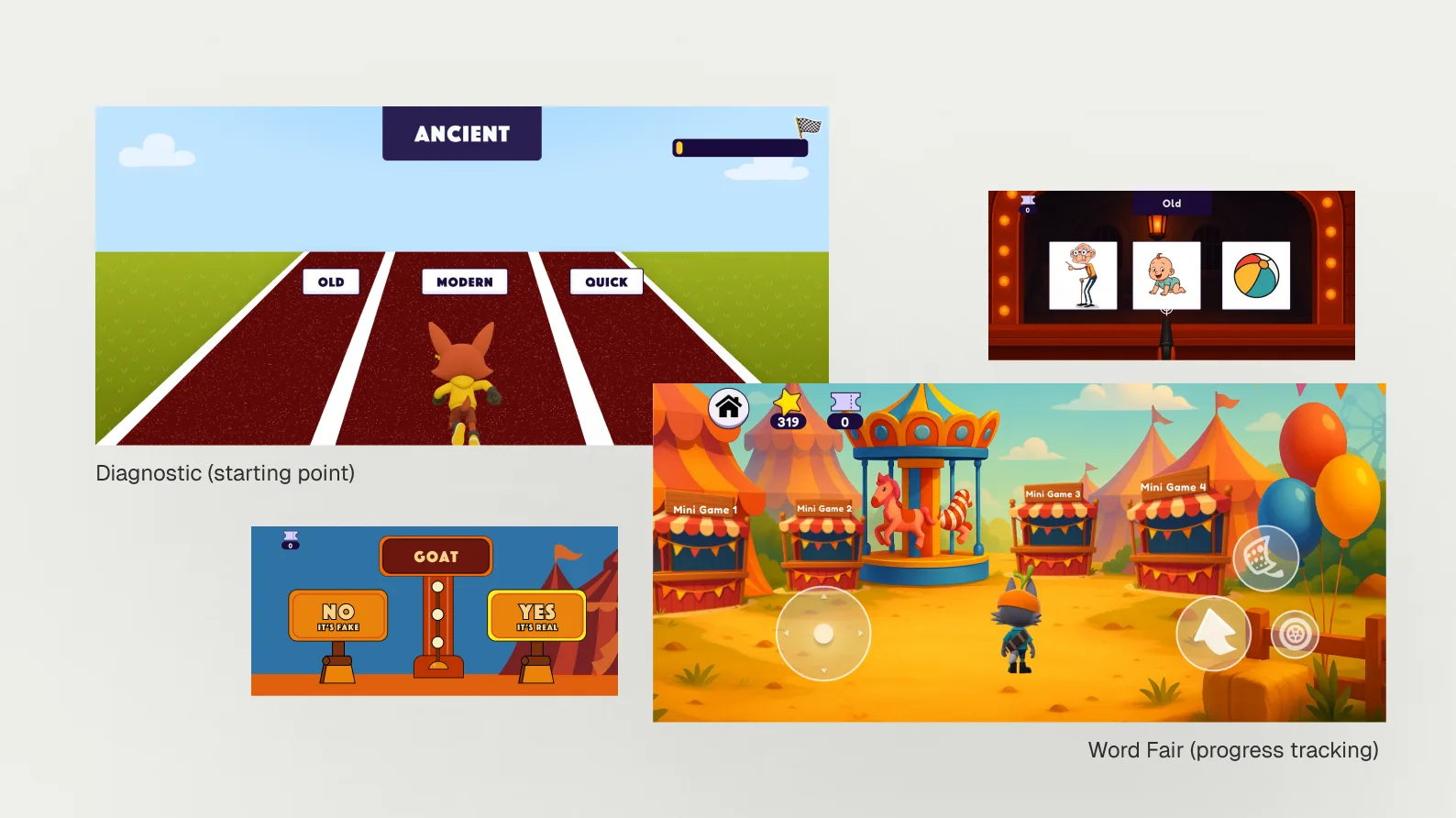

I designed the diagnostic runner flow in Figma, focusing on how learners moved through questions, received feedback, and completed the session. This design served as the blueprint for a teammate to build a functional web prototype (MVP). We used the MVP in playtesting with children aged 7–13, which allowed us to observe real interactions beyond a clickable mockup and validate the feasibility of the adaptive runner design.

What testing revealed

Across two rounds of MVP playtesting with children aged 7–13, the diagnostic proved intuitive, but testing surfaced several stress points that reduced motivation:

- Kids sometimes took too long, answering fewer questions than expected.

- A fixed 2-minute timer created pressure, especially for younger learners.

- Some question wording caused hesitation.

These findings directly informed the next round of refinements.

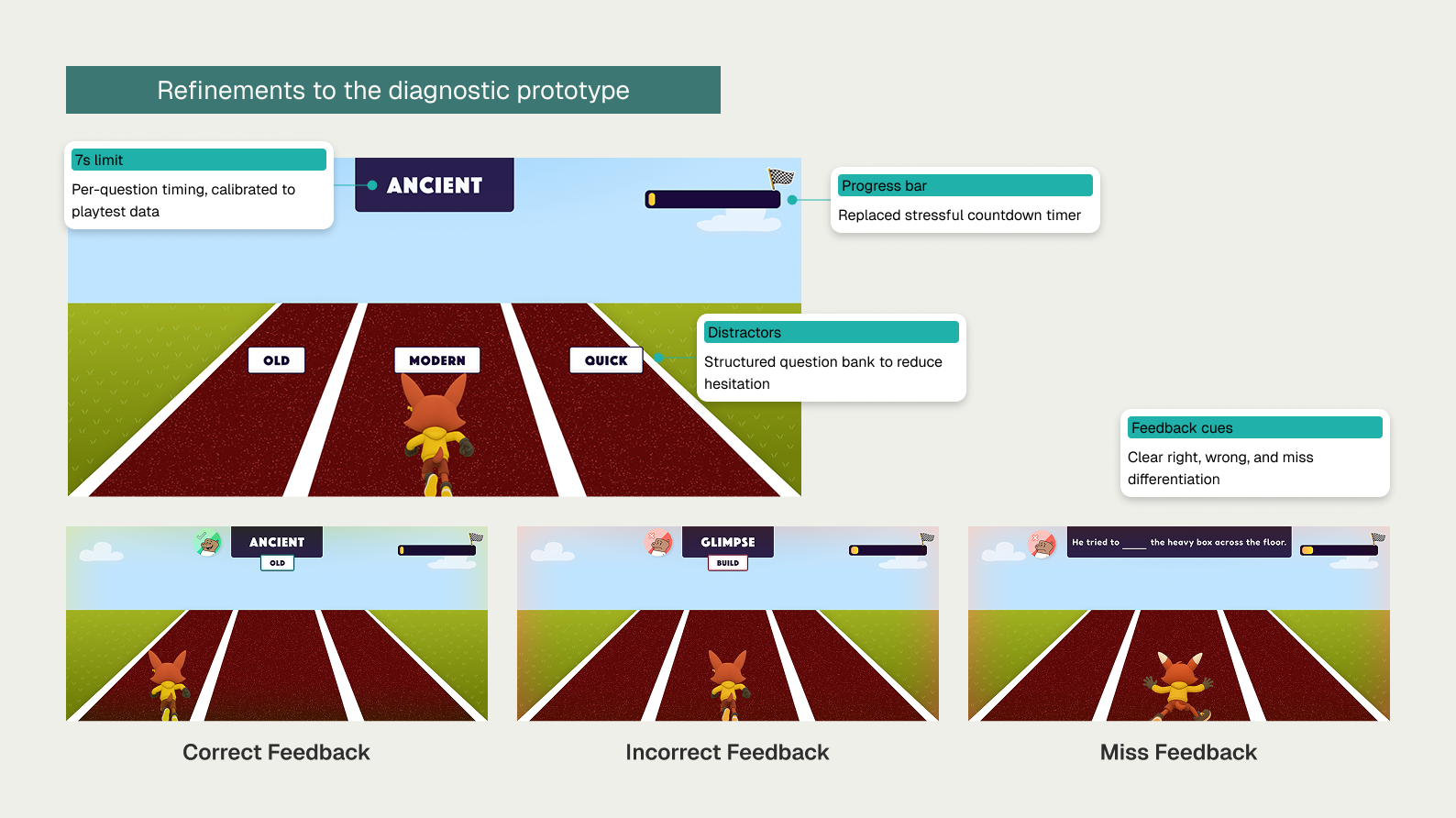

Refinements made it smoother and motivating

To balance accuracy with engagement, I refined the diagnostic design based on playtesting insights:

- Introduced per-question time limits (~7 seconds, calibrated from observed averages).

- Structured the question bank and distractors so options were clear and hesitation was reduced.

- Replaced the countdown timer with a progress bar to reduce pressure.

- Enhanced feedback cues so right, wrong, and missed answers were more clearly differentiated.

While the diagnostic gave learners a stronger start, teachers still needed a way to track progress over time. That led us to design Word Fair — a celebratory event for measuring vocabulary mastery without breaking the flow of play.

Designing the Word Fair framework

I created the event flow for Word Fair: when it would happen, how it was announced, and how players would enter a new carnival plaza for one session. From there, the plaza guided learners through a circuit of mini-games before ending with a prize booth.

Prototyping the mini-games

Alongside the framework, we proposed six mini-games, each testing a different vocabulary skill (synonyms, definitions, word-in-context, picture matching, odd-one-out reasoning, and real vs. fake words). Once approved, I worked with a teammate to build out game mechanics and feedback interactions (right, wrong, miss).

Playtesting revealed fun but clarity issues

We ran exploratory playtests with a small group of children, focusing on qualitative feedback and fun ratings.

- Favorites: Pop the Balloons and Shooting Image consistently rated 4–5/5.

- Least favorite: Eating Contest was confusing (“I couldn’t tell the pie was hitting me”), scoring 2–3/5.

- Several kids mentioned wanting clearer right/wrong cues and more rewarding feedback.

Recommendations to the client

At this stage of the capstone, our deliverable was insights and recommendations rather than full refinements. Based on playtesting, we advised the product team to:

- Clarify feedback animations so correct and incorrect outcomes are instantly recognizable.

- Reinforce answers with sound or visual cues to make feedback more engaging.

- Make progress more visible during play, so children feel a stronger sense of reward and achievement.

These recommendations gave the client clear next steps to improve clarity, feedback, and engagement if the mini-games were taken forward.

A two-part system for diagnostic and progress

We designed Word Tag’s assessments as a connected system, giving learners a strong start and teachers meaningful checkpoints over time.

Adaptive Diagnostic

A short runner game used adaptive logic to quickly estimate each learner’s vocabulary level, so personalization began on day one instead of after weeks of play.

Word Fair

A carnival-style progress check replaced daily gameplay for one session. Six mini-games, each mapped to a vocabulary skill, turned assessments into a celebratory event that felt engaging for learners and informative for educators.

Together, these two assessments formed a research-based system that supported both personalized onboarding and long-term progress tracking — measuring vocabulary growth without breaking the flow of play.

Balancing challenge and confidence in learning play

Designing for children in a game setting pushed me outside my comfort zone. I usually work on interface design, but here I had to think about playability and motivation. I realized that making a game playable isn’t only about art or polish — it’s about designing flows and feedback that kids can actually understand and enjoy.

Through playtesting, I also saw that motivation isn’t just about making games fun or easy. Kids wanted to keep playing because they wanted to master challenges and prove their skills. At the same time, I noticed how discouraging feedback could undermine confidence. Striking that balance — enough challenge to drive mastery, but feedback that builds confidence — is exactly the kind of design tension I want to keep exploring.

This project also helped me understand my own design identity more clearly. My strength lies in designing systems, flows, and clarity that make playful ideas usable and motivating. That perspective will continue to guide me as I design at the intersection of learning science and play.